Sydney’s Water Sewerage and Drainage System – Donald Hector – Botany Pumping station c.1870

After covering the great poo-litical divide that began in the 1850’s in the History of Sydney Poo part 1, we’re now holding our breath and taking a deep dive into the next chapter. Last episode saw political games, petitions and a whole lot of poo-king around in Sydney’s dark and smelly past. Now we tackle technology, profiteering and explosions of a different kind!

Depositing sludge from strainers on Botany Sewage Farm 1892

Faith in technology

Sydney wasn’t just drowning in poo, it was drowning in the technological choices available to treat it. Engineers and politicians armed themselves with information. And they spent an awful lot of time in airtight rooms discussing the problem while the poo flowed on. About the only thing everyone could agree on was the cesspit solution was not going to suffice. The cesspit system had fallen out of favour due to an association with disease. However variations of the water closet, dry closet and pan systems were very much vying for contention. It was a pageant of the sewerage options. And like any good pageant, everyone was looking to see what had the best legs. The trouble was no-one knew for certain which option would lead them from the stench-filled horror that Sydney’s poo problem was becoming. And any wrong step could essentially lead to political suicide. Just as the water closet was built to capture and flush the effluent away into the sea of the city, the dry closet (sometimes called earth closet) captured the waste and kept it close. Treated with earth, charcoal or ash, this collected manure was dried out. The stench of the manure almost removed by the addition of the substrate, it was planned to transport this treated waste to a treatment plant for conversion to manure. The downside was it wasn’t as simple as simply pouring the waste out to sea. The pan method meant capturing urine and faeces together in a metal pan below the toilet seat. Air-tight, this form of collection method hoped to remove the fumes and the need for additional treatment. Full pans would be placed outside for collection, just like rubbish is today.

Sanitary pan with metal lid – www.powerhousemusem.com

The full, sealed pans would be taken away on the carts and new, clean and deodorised ones left in their place. This waste would also be taken away for treatment and conversion into dry cake manure. It relied on assistance and the good actions of the population. While the poo-pulation grew, so too did the anger of the population. As the battle raged over technology, a solution of sorts came to being.

General View of Botany Sewage Farm from inlet house 1892

The Sydney Farm opens

After looking over the country to the highly successful and highly profitable Adelaide Farm, Sydney councillors were keen on solving the sewerage problem while recycling the waste into money and food as well. In 1882, the government quietly resumed some 300 acres near Botany. The plan was to cart the city’s sewerage to the farm and treat it there. By 1887, it saw its first load of sewerage delivered. In its first year alone, the Sydney Farm saw 1.5million gallons of sewerage arrive daily for treatment. Divided up into 34 acre lots on rotation, the lots were used for treatment of poo. Once that lot was a full to the brim of Sydney’s poo, it began its new life – vegetable and farm animal production growth. Sydney’s sewerage had come full circle. As the waste left the bodies and travelled out to Sydney Farm for processing, the vegetables and livestock found their way to markets and back into the mouths of the population. Cabbages, turnips, lucerne and sorghum were sold to the inhabitants of Sydney or fed to pigs and cows that were. The cycle of the effluent from leaving the Sydney inhabitants to feeding them was almost a complete success. It dealt with the waste, fed the inhabitants and turned the government a tidy profit. As the people and the livestock grew fatter, so did the coffers. But then the problems of the old came back to haunt.

Too many people, not enough treatment

By 1900, the Sydney Farm was treating a whopping 3.25 million gallons per day. It was a leading lucerne provider and cows were fattening nicely on agistment around the farm. But the neighbours were starting to complain. The stench was horrendous and the overflow enormous. It failed to drain when it rained. It failed to drain due to volume. And residents were muttering about health problems and law suits. Poo slipped and slid out of the farm as the politicians slid from grace. Slowly but surely, as more lots were resumed to treat sewerage, the farm itself was no longer making money. So high was the volume that land was drenched with effluent. The cost, the lack of treatment and the hideous smell saw the farm surrounded by even more debate and angst than the previous outfall experiments. An outbreak of swine fever in 1905 saw the only profitable arm of the farm, the piggery, shut down. By 1908, what farming had been left was halted as the river of poo increased from 3.25 gallons to 6.75 gallons daily. People were angry. They rallied and they fought. And it looked for quite some time that Sydney may even have a riot on its hands if something wasn’t done to stem the tide of dissent and effluent. The powers that be knew the Sydney farm experiment was over. By 1916, the Sydney Farm was closed without fanfare. Profit gave way to the need to deal with the sewerage effectively. Pipes were opened down along the coastline to push the poo out to sea and as far away from the city as possible. By 1920, much of Sydney’s waste was finding its way out to sea via Malabar, Bondi and North Head.

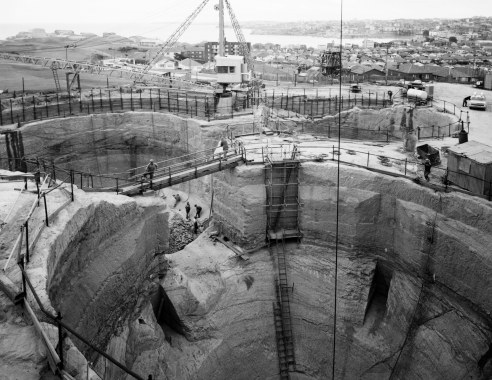

Sydney’s Water Sewerage and Drainage System – Donald Hector – Bondi Sewerage Treatment Works under construction in 1984

Today’s journey

Thankfully for us, health of the inhabitants and maintaining a clean coastline are just as important as managing our waste. Sydney Water collects from Sydney, the Illawarra and the Blue Mountains and treats this waste at 16 different sites from as far south as Shellharbour and as far North as Brooklyn, as west as Penrith and as east as Bondi. 1.3 billion litres of wastewater from over 1.7 million homes and businesses find its way to a treatment plant along the circuit every single day. From a plumbing perspective, this is nothing short of a miracle. Dealing with our household waste water, storm water drain overflow and everything in between is a day in the life of these waste water treatment sites. These plants work in an interconnected web of different treatment skills and resources to get the job done. Doing so without major issues and without stinking up the joint like treatment systems of old is a true feat of engineering.

Bondi Beach from Above – the sewer vent was built here in 1910